From that year, Huang began to help the missionaries with translation

and literary work, since he had received a basic education in the

Confucian classics and wrote well. Apart from helping to translate the

Bible, from 1874 Huang became the key helper with a Chinese newspaper

the missionaries started that year called Zion’s Messenger (Huanshan

shizhe yuebao). Huang used the newspaper as a platform to write articles

advocating a number of modern reforms. His was one of the first Chinese

voices to call for using vaccinations against smallpox, as well as for

putting an end to the practice of foot-binding. In addition, he was a

strong advocate of mission education who favored instruction in English

so that Chinese Christians could tap into Western knowledge and the

field of commerce. Education of women was part of his vision and he

established two private schools, one 1873 and the other in 1885, to

educate his own children, including his daughters.

Starting from the early 1870s, Huang decided to prepare for China’s

traditional civil service examinations. He chose this course because he

saw the numerous conflicts that Chinese Christians experienced with

local society and how they were discriminated against and marginalized

by local gentry. Huang believed that if there were Christians who were

members of the gentry it would improve the situation. He studied hard

and in 1877 obtained the basic

shengyuan degree, which was followed in 1894 by the much more difficult

juren

degree. This was quite an achievement, given the stiff competition for

degrees in the latter part of the Qing dynasty. When Huang traveled to

Beijing in 1895 to take exams for the highest level

jinshi degree

(which he never obtained), the Sino-Japanese War was underway, and he

suffered the pain both of China’s defeat and the loss of his younger

brother, who was a sailor in the navy. Huang then joined other scholars

in Beijing in support of Kang Youwei and his call for China to reject a

peace treaty with Japan and to immediately seek ways to strengthen the

nation.

Upon returning to Fujian, and in light of the dangers facing his

country, Huang decided to leave his work at the Methodist Episcopal

mission and instead seek to promote a Christianized China through

political and educational reform. To this end, in 1896 he used his own

funds to launch a secular Chinese newspaper called Fubao, which was the

first newspaper started by a Chinese in Fujian. It was a two-page paper

published twice a week and it advocated adoption of such reforms as a

parliamentary system and a free press. However, after a year he had to

shut the paper down because it was losing money.

Three years later, Huang was in Beijing again to take the

jinshi

exams when the 100 Hundred Day Reform movement led by Kang Youwei

started. He not only actively supported this, but through a friend from

Fujian who was very close to Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, he became

directly connected with the leaders of the movement. He himself

submitted eight petitions to the Guangxu Emperor, one of which

recommended adopting pinyin to help with the study of Chinese

characters. However, when the reform movement met with a conservative

backlash and some of its leaders were arrested and executed by the

government, Huang was forced to flee quickly to Fujian, since he was

number eleven on the most wanted list.

Shortly thereafter, Huang decided to start a new settlement of

Chinese in Malaysia in order to escape China’s despotism and Fujian’s

poverty. While in Singapore considering where he might establish such a

colony, Huang met Sun Yatsen and the two soon became good friends.

Huang’s translation into Chinese of a book on American history won Sun’s

respect, and Huang admired Sun’s democratic ideals and commitment to

Christianity. In 1901, Huang traveled with settlers from Fujian to Sibu,

where he founded New Fuzhou. Before long New Fuzhou had a population of

over one thousand Chinese, two-thirds of them Christians. Huang spent

the next three years attending to myriad administrative tasks needed to

get the community established. Unexpectedly, in 1904 he returned to

Fujian, in part because his administration of the settlement did not

generate enough profit to satisfy the local ruler who had supplied the

land.

Back in Fujian, Huang founded the

Fujian Daily News and was a

leader of Fujian activities during the nation-wide anti-American boycott

of 1905, which protested the adoption of exclusion laws by the United

States preventing Chinese laborers from entering the country. While he

avoided harsh anti-foreignism, Huang did not hesitate to strongly and

publicly condemn the American policy.

By this time, Huang had also shifted his political views from favoring reform, as he had in 1898, to supporting revolution.

Young J. Allen, the missionary editor of the influential Chinese language

Globe Magazine

in Shanghai, was a key person in convincing Huang that support for

revolution was a legitimate Christian position. Huang then began to

distribute tracts calling for revolution and became an active supporter

of

Sun Yat-sen,

sending information on revolutionary activities in Fujian to Sun’s

agents in Singapore, who then reported it to Sun in Tokyo. Huang joined

Sun’s Revolutionary Alliance in 1906 and was a key figure in planning

the Huang Gang uprising and recruiting many of those who participated in

it.

From 1907 to 1911, Huang focused primarily on promoting educational

reform by founding 34 Chinese secondary schools in the Min County region

of Fujian, which he made sure taught Western subjects and inculcated

nationalism. Also, in 1909 he was elected to the Fujian Provincial

Assembly, which was part of the constitutional reform program that the

Qing government had been forced to adopt. Huang became one of the

leading members of the legislative body and he proposed numerous

reforms, for instance to ensure better use of Fujian’s natural

resources, to counter opium and gambling, and to introduce penal reform.

In 1911, after the 1910 Wuhan Uprising began to unravel Qing rule in

China, Huang began to spread revolutionary ideology among students at

the Methodist Anglo-Chinese Academy in Fuzhou, where he was Dean. In

addition, he established the Fuzhou Qiaonan Physical Training Society as

a front for the Fujian Revolutionary Alliance where it could train the

students who joined the movement. On the 9th and 10th of November 1911,

Huang and the Fujian Alliance fought against and defeated the Imperial

Army in Fuzhou with the help of these students, and thus brought Qing

rule in the province to an end. As a supporter of Sun, Huang was

appointed head of the Board of Communications for the provisional Fujian

government in November 1911, but his high-level public service soon

came to an end when Yuan Shikai deposed all Sun’s supporters in

September 1912.

Huang spent his remaining years engaged in various community

projects, serving as head of the Board of Trustees for the Fuzhou YMCA,

helping to edit a political newspaper, and being sought out as an

adviser to government officials. He held his Christian faith to the end.

As he lay on his deathbed, he asked his wife to hold up a picture of

Christ for him to see, and asked that the picture be laid on his chest

as he died on 22 September 1924.

Huang Naishang was one of the most influential and impressive Chinese

Protestants of the Imperial era. His experience in ministry and his two

decades assisting missionaries in literary work instilled in him a

strong faith and an informed Christian worldview, as well as a

familiarity with modern knowledge. His Confucian upbringing and success

in the civil service examinations were extremely rare for Chinese

Christians at the time and allowed him to have significant social

influence. Huang used this influence to seek the reform and

Christianization of Chinese society through educational and political

change. He described his motivation to do these things as Christian

altruism, which combined Christian notions of personal sacrifice for the

benefit of others with Confucian ideals of public service. Huang’s many

years of ministry and community involvement touched numerous lives and

did much to enhance the credibility of the church and of Christianity in

China.

Three daughter of 黄乃裳:

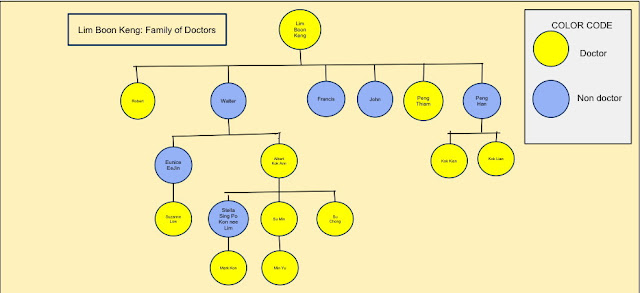

1) 黄端琼 Margaret Wong Tuan Keng married to Lim Boon Keng

2) 黄淑琼 Ruth Huang Shu-Chiung married to Wu Lien-Teh

3) 黄珊琼 Huang Shan-Chiung married to Seow Poh Quee

.jpg)